Eyewear

Retrospective

VOLUME:1JAN 12, 2022

Fig. 01

/0472847f025802ce6c4dd3.jpg

Prologue: First Glimpses

Every single object in our lives, even and perhaps especially the ones we take for granted, has its individual history. Ironically, in the case of modern eyewear, that story is notably hazy.

Stories of early eyewear abound, but two are commonly referred to. One tells of Nero, Rome's fifth emperor, a patron of athletics and the arts (and arranger of his own mother's murder) who supposedly watched gladiator matches through polished gemstones. Then there were the 12th Century Chinese judges who shielded their eyes from the sun (and defendants) with slabs of smoked quartz.

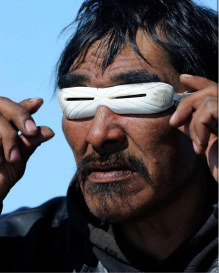

But the first to really get sun-protective eyewear right were the Inuits. Faced with the everyday threat of snow blindness in the bright and highly reflective Arctic environment, these native peoples engineered goggles FIG.01 from wood, bone, walrus tusks, and caribou antlers by carving these materials into oblong bands and making long, narrow slits over each eye and using leather ties to fasten them to their heads.

However elementary the design may seem, it provided adequate protection and remarkably good peripheral views. Unlike Nero and the judges, who stared as much at those glassy stones as through them, the Inuits based their bone goggles on necessity and function; they were a tool to help them hunt and survive in the world's harshest environment. The design still works today, too — in a pinch, mountaineers can make emergency goggles from duct tape with slits over the eyes — and eventually, a function-first philosophy would set the eyewear industry down the avalanche path that's carried it through the years.

But hand-carved bone goggles probably aren't what come to most minds as modern eyewear. The thing is, all the way up until the 20th Century, specs remained medical and mundane. Leave it to a businessman to see how they could be so much more.

Fig. 01

1222985_81_110880_ZqIAHWZFu.jpg

I. Looking Through Lenses

The industrialist in question was Sam Foster. In 1929, Foster offered up for sale a lifestyle accessory to Atlantic City beach-goers that they'd only recently begun to see donned by Hollywood's glossy stars — mostly to protect their eyes from bright studio lights — and likely never considered affording themselves: sunglasses. They helped with the sun, sure, but they were also fashionable. This, Foster realized, was a shift worth some money; previously guided solely by material technology and prescriptive necessity, eyewear could now evolve along a new path defined by aesthetic, taste, and trendiness.

Function and performance, however, continued to advance along a parallel course, and to pick up speed. Foster was only able to bring his shades to the masses by adopting the then-novel technology of injection molding and a new-ish material called celluloid, which was created in response to a billiard ball manufacturer's advertisement of a $10,000 prize to the inventor who came up with a worthy substitute for the elephant ivory it had previously been using. Without celluloid, there'd be no mass-produced sunglasses (nor any elephants, either; the going production rate was only four or five balls per tusk).

Three more 1930s innovations prepped eyewear for a century of proliferation. There was the high joint, which brought the attachment point of the temples from the center of the frame to the top corners. Then there was a subtler update called pantoscopic tilt, in which lenses curve down and inward toward the face instead of sitting flat across it. The third came in '36 when physicist Edwin Herbert Land created a lens treatment FIG.02 to reduce optical glare; he called the shades polarized, and a year later founded the Polaroid Corporation.

Each of these innovations concerned functionality, though the first two, in changing the shape that a pair of glasses might take, hinted at a future where aesthetics could guide design as forcefully as utility.

With all this progress, it's no surprise that the 1930s also brought about the first pair of truly iconic sunglasses. Like GPS, cargo pants, Duct tape, and so many now-everyday products, they were the result of a collaboration with the US military.

Commissioned by the Army Air Corps, Bausch and Lomb — the same company known for contact lenses now — utilized both the high joint and pantoscopic tilt, combined with teardrop-shaped lenses and a dark green tint to make new anti-glare sunglasses for pilots. B&L called them Ray-Bans, the public called them aviators.

Aviators were made specifically for flying, but that didn't stop Bausch and Lomb from selling them to civilians for roughly $4.75 a pair (if you find a pair for less than $163 today, check to make sure the logo doesn't smudge off). The company was beginning to understand that form was becoming more significant than function, even though its designs were still wholly based on the latter.

By the end of the 1930s, mainstream culture had adopted sunglasses as much more than just corrective and protective — they were in implement of style. But the optical companies that produced the bulk of them clung to custody for another two decades.

Fig. 02

original_e36c6127a573fe9d0e8ea5df0055e0cb.png

II. Eyewear's Golden Age

Then, in 1953, American Optical Company made the unprecedented decision to work with fashion designer Claire McCardell to create the first line of sunglasses designed by a fashion designer. McCardell had become well-known for her distinctly American (read: anti-Parisian) clothing designs, which eventually earned her credit as the creator of American sportswear. She was also a member of Sports Illustrated's founding panel.

McCardell's history with active leisure might imply that the inaugural designer-first eyewear collection would continue the established preoccupation with performance. Instead, she used the line to embrace the cat-eye, a distinctly feminine frame shape with accentuated upper corners (thank you, high-joint) that had been invented in the '30s. Some featured subtle corners and rounded lenses, others were angular with narrow lenses; all intended, like her clothing, to modify the wearer's appearance like "make-up for your eyes," according to an ad for the collection.

AOC's collaboration with McCardell might be standard operating procedure today, but at the time, it was landmark. Not only because it was successful, but because it confirmed to the companies that controlled the development of eyewear that fashion could lead design while utility worked in the background; if sunglasses cut glare or protected pupils, that was just an added bonus. After this, how and why a new collection of eyewear emerged would be the result of an entirely new set of rules outlined by fashion designers, magazine editors, and Hollywood stars.

The unwavering popularity of the cat-eye style over the decades following Hollywood's so-called Golden Age proved just how potent these rules were. Marilyn Monroe wore cat-eye shades, Frida Kahlo had a gold pair, and Audrey Hepburn solidified her status as an icon while wearing an oversized set in Breakfast at Tiffany's. An increasingly fast-paced culture, charged up by the advent of the home color TV in the mid '60s, ensured that every woman in America saw these idols — and what sunglasses they wore FIG.03.

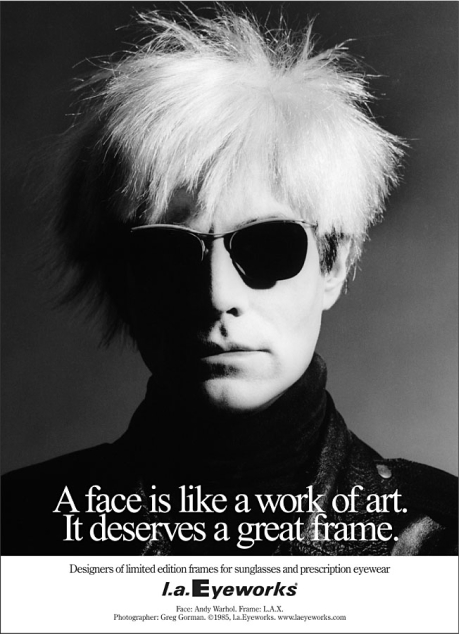

Men weren't left out, either. In 1952 Bausch and Lomb set eyewear designer Raymond Stegeman to the task of creating an equally modern frame for Ray-Ban, which had become a brand in its own right. Stegeman took inspiration from Eames chairs and Cadillac tail fins to come up with the Wayfarer, an acetate alternative to metal frames and a masculine answer to the cat-eye made possible by innovations in plastic molding technology. Then the wheels of the culture machine did their turning: Andy Warhol wore them, as did Bob Dylan and James Dean; the shades Cary Grant famously wore in the 1959 thriller North by Northwest weren't Wayfarers, but they were close enough to cause some helpful confusion.

Fig. 03

583_lae_andy_warhol_1985

III. Looking at Lenses

The Wayfarer was hugely successful as a result of the new fast rate of culture creation, but when its popularity waned over the proceeding decades, it also proved itself a casualty of that speed. When designers like Pierre Cardin abandoned the notion that eyewear had to have a corrective element, it allowed them to play with an entirely new set of forms that had far less to do with looking through sunglasses than looking at them.

This idea created a new ecosystem of coexisting trends. In the sixties, John Lennon brought back the old pre-high joint circular frames, this time with colorfully tinted lenses, to a growing league of hippies and psychonauts. At the same time, others wore big, chunky frames filled with circular or squarish lenses, a style that got the seal of approval from none other than the first lady herself, Jackie Kennedy.

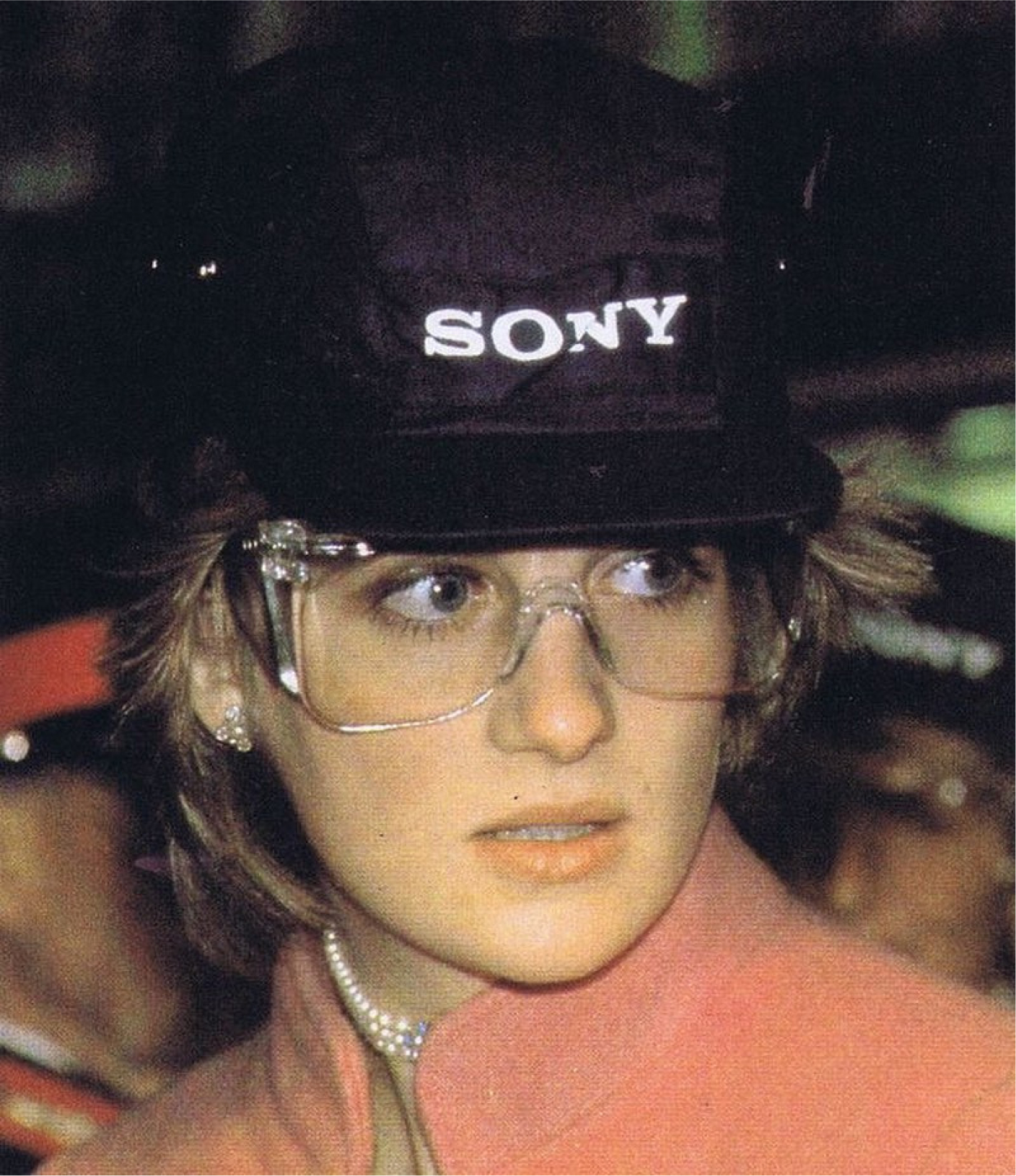

The variety in style they allowed for not just in shape and size but in color and material — designers even began decking them out with rhinestones — made for endless options. Just look at photographs of Elton John from the seventies (and beyond) for proof. Google "Princess Diana sunglasses." FIG.04 And let's not forget the massive, safety goggle-inspired shields that Arnold Schwarzenegger rocked in Terminator (they're called the Gargoyles Classic).

Fig. 04

bf12fdf8cb675a336db6d6.jpeg (left)

366221e3-6b82-46e9-a6b2-061c004aba15.jpg (Right)

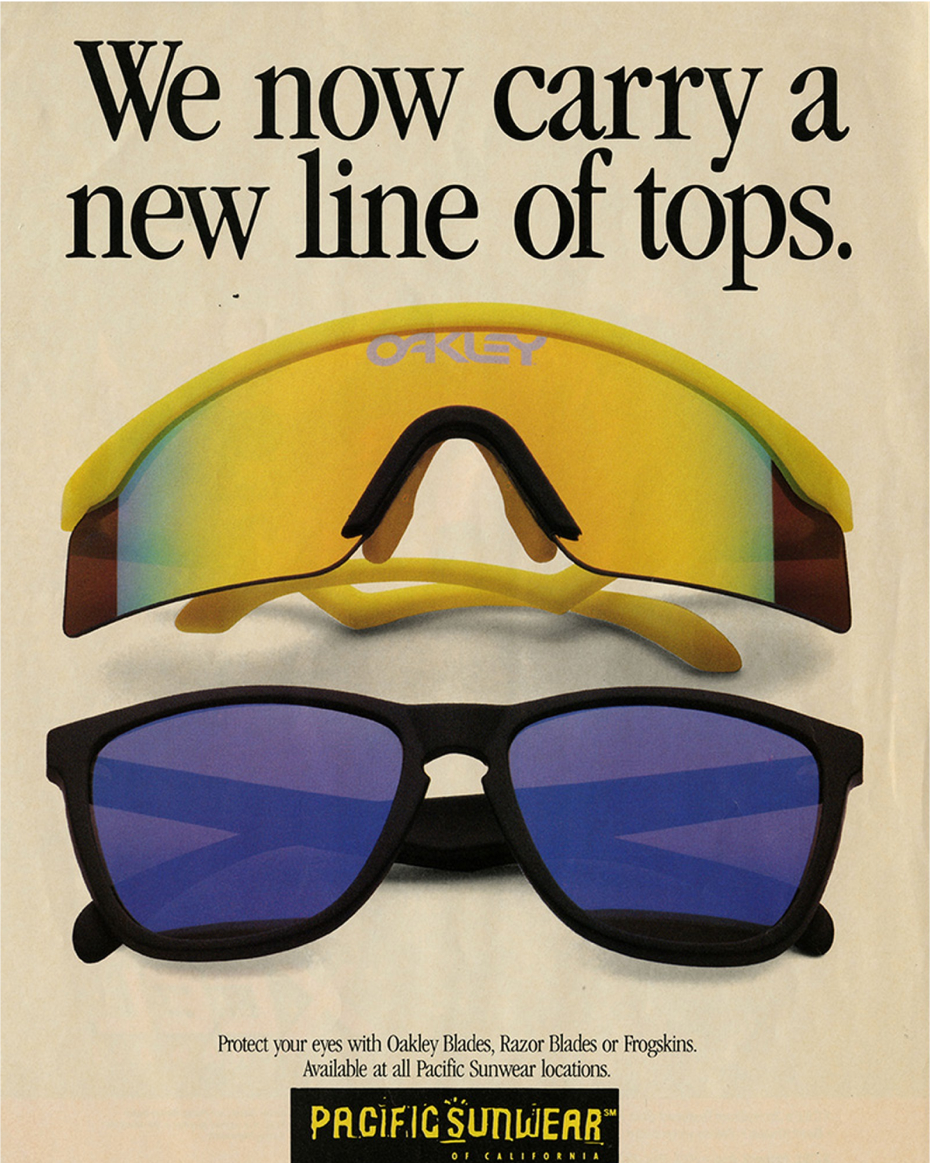

IV. The Oakley Effect

But while Hollywood and fashion designers — not to mention the powerful financial forces behind them — continued to decouple eyewear from its old connection to eyesight, a small cadre of inventors and entrepreneurs never forgot that sunglasses could do more than change the shape of one's face.

In 1983, a man named Jim Jannard made a fateful sales trip from San Diego to Los Angeles. For a decade or so, Jannard had been selling motorcycle gear, BMX handlebar grips, and dirt goggles FIG.06 to a growing population of adrenaline junkies. As he drove the California coast with the setting sun beaming into his periphery, Jannard imagined what might happen if he brought the wraparound design of goggle lenses into a smaller set of frames. Then he went home to his workshop and made the object he was imagining with some scissors, tape, and a bent coat hanger.

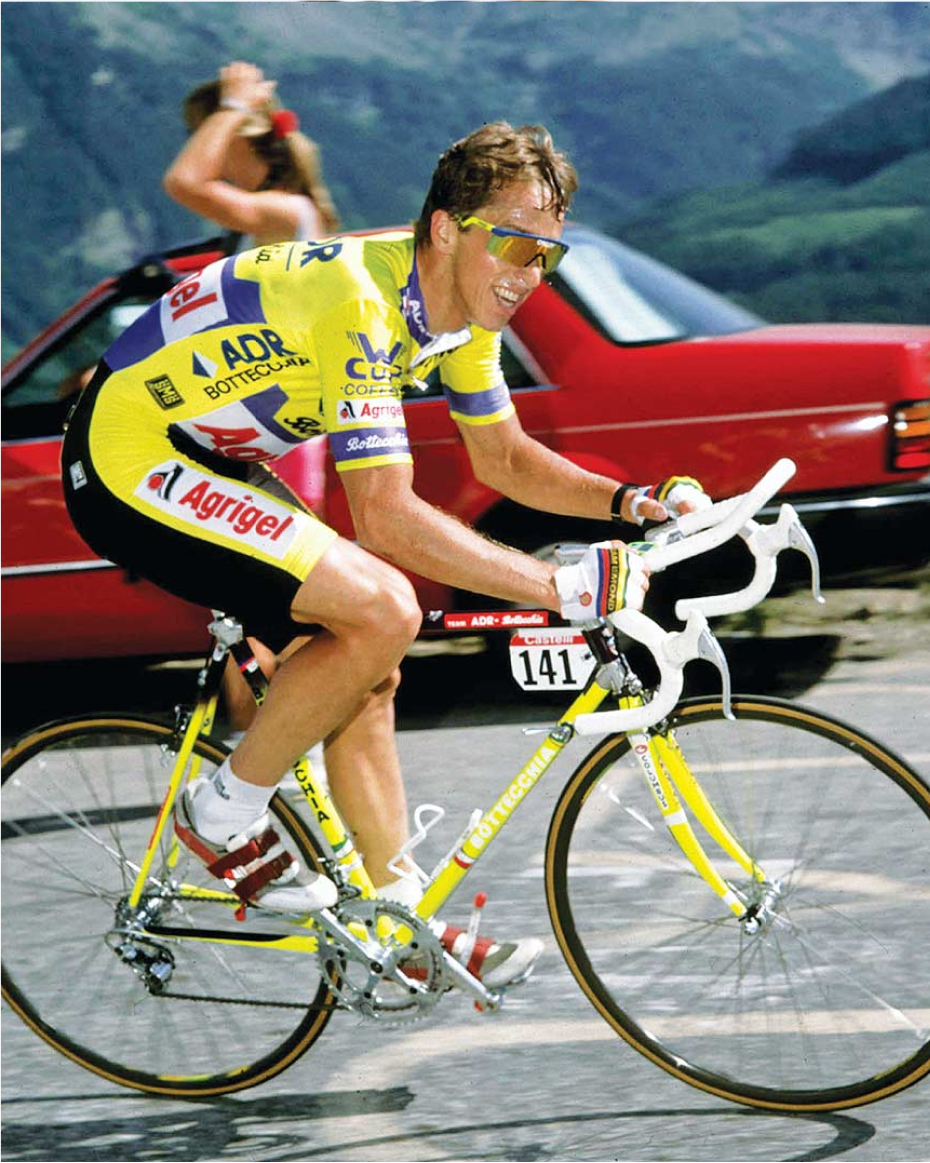

Jannard and his company, Oakley, called the production model of those sunglasses the Eyeshade. Their lens did look like a smaller goggle lens, but without the full face-seal foam and frame. After so many years of fast eyewear evolution, these were unmistakably new, the first performance sunglasses — a new category of eyewear made with the explicit intention of improving the wearer's capabilities in a sport or activity. This new type of eyewear defined itself against the casual and everyday, and even popular style FIG.07.2. Their fate, along with Oakley's, were simultaneously sealed when pro cyclist Greg LeMond wore a pair of Eyeshades through to a second-place finish in the 1985 Tour de France FIG.07.6.

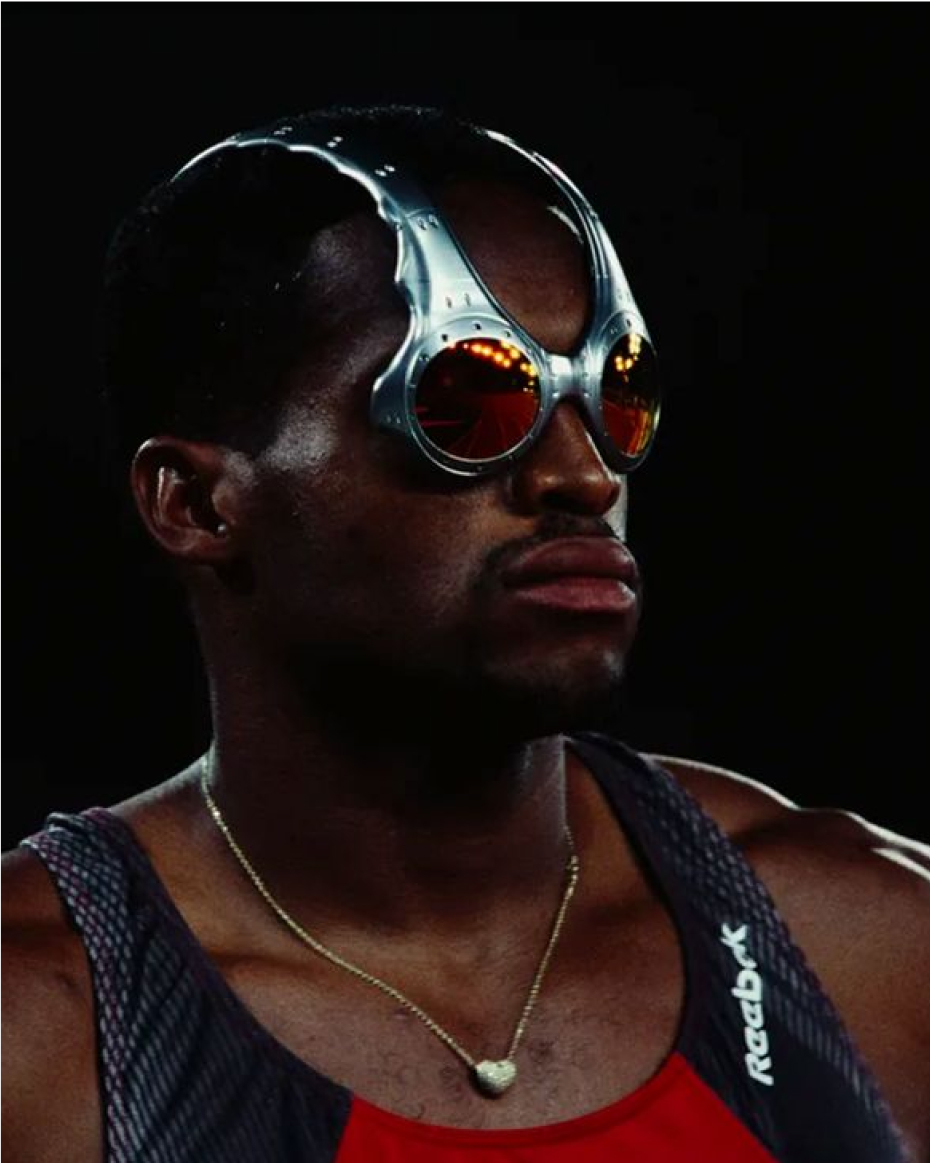

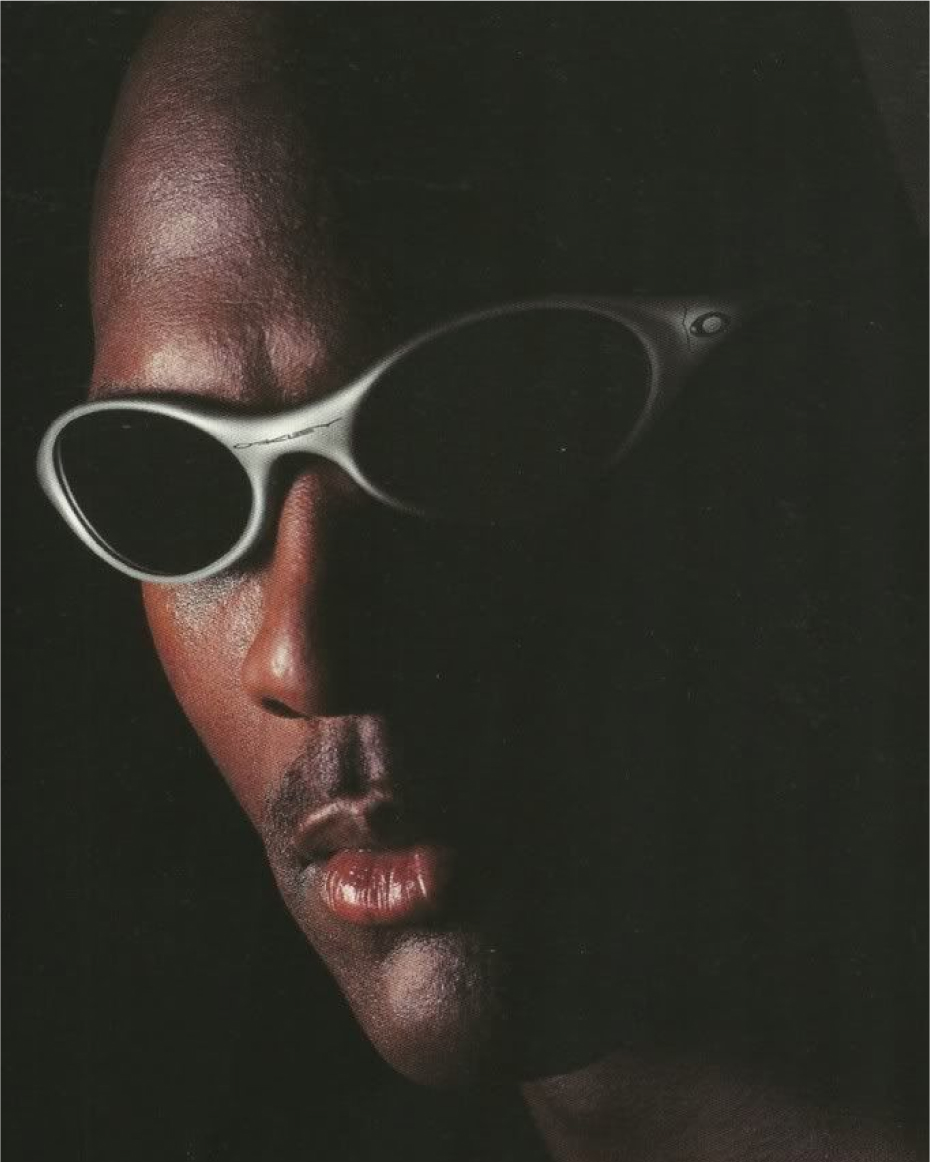

More performance brands popped up — Look, Briko, and Rudy Project all gained traction in and out of pro cycling's peloton — but Jannard and Oakley were always far out front. They showed just how far in 1994 with the release of the Eye Jacket. The frame is almost the antithesis of the goggle-like shield lenses, commonly called wraparounds, with which Oakley defined performance eyewear; two oval lenses, small, just large enough to cover the eye sockets, sit in a narrow curvy frame that, in the year of their release, could only be described as futuristic FIG.07.3.

And they were. The small sunglasses had all the tech of top-tier performance models, like impact and UV protection, and high-def optics. They were also the first sunglasses designed entirely on a computer-aided design program and the first prototyped on a 3D printer (NASA bought the first stereolithography 3D printer, Jannard bought the second, so the story goes).

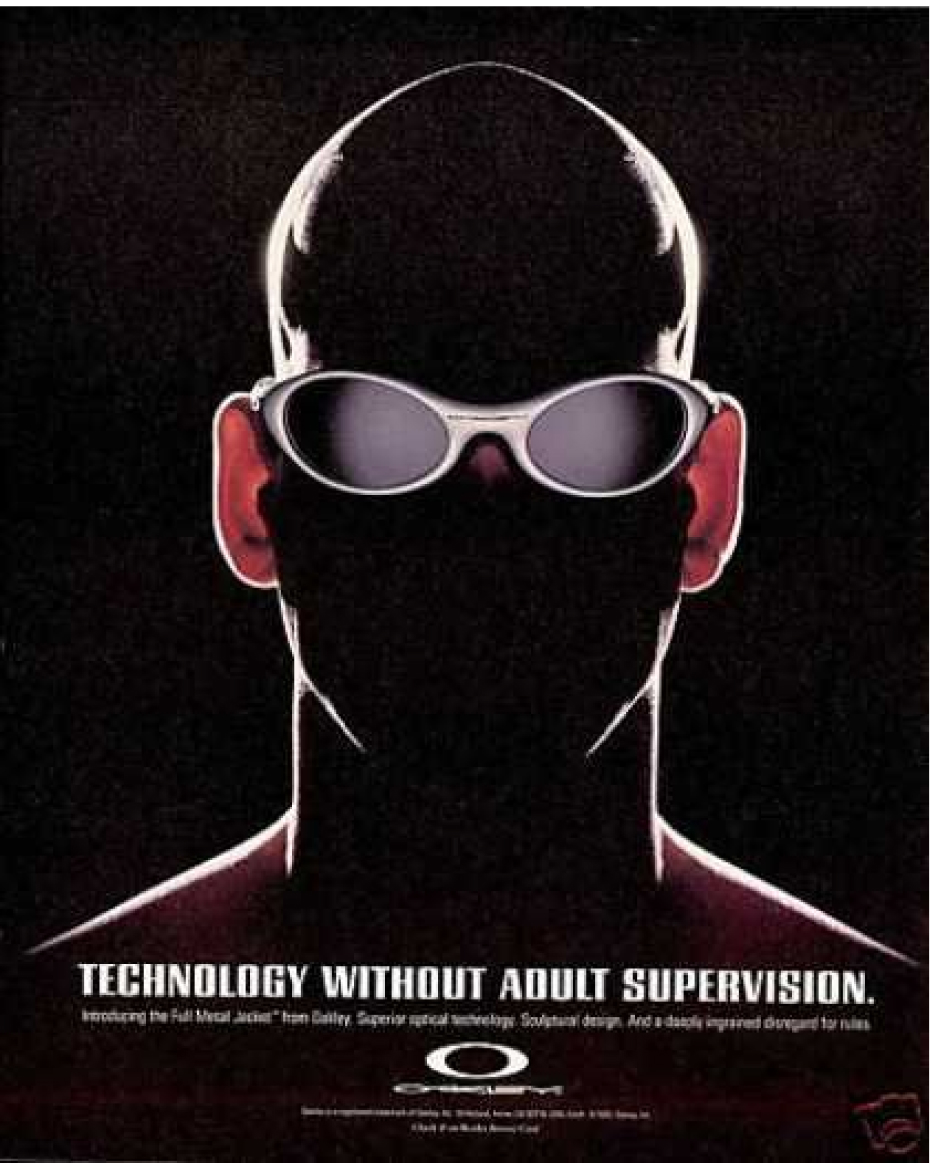

An ad for the original Eye Jacket pictures a person silhouetted into darkness that obscures all facial features except for the figure's outline FIG.07.1. The Eye Jackets he's wearing come through clear though, silver frames with dark lenses. And everyone knew who he was anyway: Michael Jordan. Jordan became the face of the Eye Jacket despite the portrait and an Oakley devotee who adopted the frame's successors, most notably the X Metal Romeo, which brought sharper angles and additional lines to make a form that was even more explicitly futuristic.

Jordan also represented the apex of a shift FIG.07.5 that occurred in the latter portion of the 20th century, wherein athletes, artists, supermodels, and even political figures, not just Hollywood stars, could become the prototypes of cool, the shepherds of style. Just as the number of possible combinations of frames and lenses expanded toward limitless, so did the types of people who might help turn any single one into an icon. (For one more potent example, check out the Oakley-mullet combo Andre Agassi sported in a 1992 Davis Cup tennis match FIG.07.4.)

Fig. 05

historical-clarity-oakleys-lens-tech-keeps-getting-sharper-13.jpeg

Fig. 06

2255b9c95451bd2fbcd69c62df0372e8.jpeg (top left)

jpg.jpeg (Bottom left)

historical-clarity-oakleys-lens-tech-keeps-getting-sharper-11.jpg (top center)

1a018e054ecd67f66ad48047069ebbea.jpg (Bottom Center)

oakley-overthetop-inline-2-1596721983.jpg (top right)

LemondTdF89OMTT-@PhSport.jpg (bottom right)

V. Eyewear's New History

If the point at which eyewear entered modernity is the point at which its link to material technology and function, so tightly wound before, began to fray, weathered by fashion and commercialization, then it's fitting that its braided history has arrived at an end made up of a multitude of loose ends. They overlap each other, double back on themselves, obscure and complement each other, revealing themselves to be what might look like a knot but is certainly a strange, beautiful, and yes, unfinished, pattern.

Now, the guiding cultural force that Hollywood and television once commanded is fractionalized amongst the Internet's innumerable corners: blogs, newsletters, Instagram aggregate accounts, subreddits, magazines that have never (and will never) come out in print, and so many others. You've felt the result — culture now runs at a blistering pace; miss a product drop and risk missing an esoteric yet crucial reference point in the future conversation. In the 21st century's current phase, creating a set of frames that can catch the attention of an entire population a la aviators is impossible.

Fig. 07

ae4df61d6abf8b02ff34b6.png

6a34027f163804eea521ad 1.jpg

40181840538b49775d2c72.jpg

But neither is it necessary. This same fractured information ecosystem has proven to be fertile ground for a proliferation of subcultures of every specificity, and its hyper-connectedness makes them visible to an entirely new set of brands that are reverent of yet unburdened by the past, and eager to forge eyewear's New History.

It's these conditions that allow for the rise of a brand like District Vision, which makes performance sunglasses for running, cycling, and other pursuits, and, in keeping with current conversations around sport, imbues each pair with the tenets of mindfulness. It doesn't hurt that District Vision's sunglasses are sleek enough to wear in casual settings, too, and it's no coincidence — DV's founders are former fashion industry professionals. The barriers that once separated performance from fashion are almost broken down entirely. It's neither ironic nor surprising when a brand like Sweden's Chimi, known for (relatively) affordable luxury, releases a line of ski goggles as capable as any in the case at the local gear shop. Or that a high-concept label like Botter would redesign swim goggles and snorkeling, two products that have been neglected and mostly unchanged for decades. (Further blurring the lines, Botter also runs a coral nursery off the coast of Curaçao.)

It's all too apparent that to create eyewear's New History, designers and brands can't help but draw on the old, imbuing eyewear with the pastiche of postmodernism, allowing a moment to matter more than any brand or frame. Materials and performance continue to progress, but decades have passed since such features have led design all on their own. Still, the archetypes of function remain clear in every new pair, with every step forward containing at least a rearward glance at the past.

Words by

Tanner Bowden

04.11.21

(c) illo.system